Is It Ever OK to Keep Marine Life in Captivity?

Most diving enthusiasts and indeed dive professionals already have a very definitive answer to this, and, no surprises here, it’s generally a resounding no! However, we live in an age of increasing awareness, so this debate is no longer confined to discussions on scuba diving forums and in dive centre classrooms as it once was. The rise of social media and its inherent ability to share and spread stories and petitions, along with the popularity of documentaries like Blackfish and The Cove, has meant that awareness regarding the rights of marine animals has spread more significantly in our worldwide population in recent history. Plus we are generally seeing a shift in mindfulness when it comes to conservation matters in general. The no plastic movement has gained an incredible following in the last few years alone, and today’s youth seem very much more aware of the fragile nature of their surroundings than in generations gone by. But we digress….

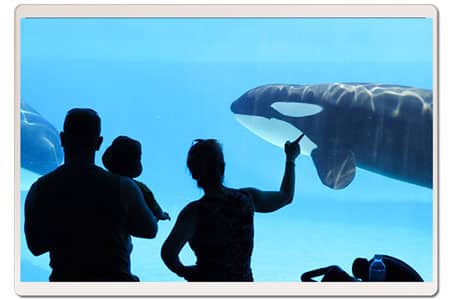

Right now we bet you are imagining huge water pools in amusement parks and zoos filled with mammoth marine life species like Orca Whales. Maybe you have even visited one of these yourself? After all, many of the world’s leading marine biologists’ dreams to become more involved with the ocean came from childhood visits to such attractions. We’re not just talking about cetaceans though, but marine life in general.

What is a cetacean you ask? The term refers to all warm blooded carnivorous mammals that inhabit our oceans – so essentially whales, dolphins and porpoises. Some are surprised to learn that sharks do not fall into this category, but it is true! In reality a shark is really just a very big fish! An easy way to tell the difference is that cetaceans have lungs and need to breathe air at the surface just like we do, which is why you see dolphins and whales from sea level as well as beneath the waves. The spray you see from the blowhole of a whale for example, is simply the creature exhaling the warm air. So the blowhole is essentially their version of nostrils. Another way to tell the difference is in the noise they make. But don’t get us started on fish noises, that’s a whole other blog!

Anyway… returning to the topic in hand, indeed many aquariums around the world do not keep cetaceans in their tanks. Yet some do keep sharks, as well as many other varieties of fish species. So our question does not relate specifically to just the ‘big stuff’, but to marine life in general. Is it ever OK to keep marine life in captivity?

So, let’s work on the assumption that most sound minded souls would agree that keeping marine life – and in particular cetaceans – in captivity is wrong. But is it ever OK?

Let’s hear it for the No’s

There are several and varied reasons why marine life should not be kept in captivity…

Lack of free movement

When in their natural environments, marine species can travel huge distances on a daily basis. The most notable examples are dolphins, sharks and whales. The exact distance any species would travel on a given day in the wild would be largely determined by their food source, however it is estimated that dolphins can swim up to 128 kilometres per day, whales up to 225 kilometres per day and sharks up to 112 kilometres per day. Even smaller, reef swelling fish that do not migrate still cover a lot of distance. Any diver who has exerted all of their energy – and air supply! – chasing tropical fish like Butterfly Fish or Banner Fish around a dive site trying to get that perfect photo will testify to that. So just because the fish itself is smaller, and as is kept in a tank of comparative scale, it does not mean that it has enough space to move around.

As well as the general linear distance a species can cover, captive conditions also prevent them from diving as deeply as they would normally. Dolphins for example have been known to dive as deep as 300 metres, while sharks and whales have been recorded at depths of up to 3000 metres!

The inability to travel freely is widely noted as a source of discomfort for marine animals in captivity, and often leads to unhealthy conditions of their minds and bodies. As well as lowering the expected life span in general, notable issues include lack of appetite and more frequent illness. A well-known example of physical change due to captivity is in the dorsal fins of Orca Whales. The dorsal fin would normally be vertical, but with captive Orcas we see the fin droop or collapse. Attractions such as SeaWorld claim that “Neither the shape nor the droop of a whale’s dorsal fin are indicators of a killer whale’s health or well-being”, and state that this is a common issue. However this is not true of wild Orcas, and it is widely postulated that this is indeed an indicator of an unhealthy whale, caused directly by both lack of free movement and an artificial diet. Which brings us nicely on to our next point…

Unnatural Living Conditions

Ranging from the pure aesthetics of their surroundings to the food they are provided, there are many factors that can inhibit the health of captive marine life. Most artificial environments are rather sterile to say the least, and provide no stimulation for their inhabitants. Nowhere to escape or explore. Plus they are filled with extra toxins such as filtration chemicals that leave marine creatures open to bacterial and fungal infection. But at least cetaceans can survive this. Many of their smaller ocean brothers such as such as tropical fish, invertebrates, and sea vegetation cannot survive these conditions at all, and as such live incredibly short unhealthy and unhappy lives. Then of course, there are the many deaths caused by technical malfunctions and human errors:

• At SeaWorld, sixteen sharks died after workers waited too long to shut off water being pumped from Mission Bay into the aquariums.

• Fifty-four stingrays reportedly died at a zoo in Chicago because the oxygen levels in the tank fell.

• A similar incident killed more than 40 stingrays at the Calgary Zoo.

• At a Texas aquarium, hundreds of fish, including a tiger shark, died when workers added medicine to the tanks in an attempt to fight parasites.

Most captive species are fed on thawed dead carcasses, a far cry from their usual diet of freshly hunted fish. So much so that many captive species also require vitamin supplements, as most of the nutritional value of the fish they are fed in captivity is lost by being frozen.

Communication and sensory perception is also effected by being held in unnaturally confined water. Most marine species communicate via motion, electrical pulses or even bio-luminescence. However in a bizarre contrast to being able to listen and communicate with their fellow fishy friends, captive marine life are instead forced to listen to rowdy audiences, music, the clanking and banging of props, as well as the noises inherent of their artificial habitat such as water pumps and filtration systems. The very construct of their enclosures are also contra-indicative to their well being, as they are often poorly designed so that artificial sound is magnified.

We must also consider opportunities for socialisation. These would be plentiful in the wild, however it is not uncommon for large marine species to be isolated in enclosures. On the flip side, there have also been documented instances of marine animals being kept in shared tanks with incompatible species. Sometimes even with species with which they would have zero interaction outside of captivity.

Animals Captured from the Wild

Despite some success with ornamental and fresh water fish species, there has been very little success in the captive breeding of larger species like cetaceans and sharks. Because of this, the majority of captive marine life, and especially larger species, are sourced from the wild. Here’s a few facts for you:

• There are currently a total of 61 orcas held in captivity, 27 of which were wild-captured and 34 captive-born. Historically at least 165 orcas have died in captivity, not including 30 miscarried or still-born calves.

• It is estimated there are over 2,900 dolphins in captivity worldwide.

• Over 11 million fish are removed from the ocean on a yearly basis to meet the demand for public and private aquariums based in the United States alone

• 79 percent of animals held in public aquariums in the UK are thought to have been taken from the wild and put in tanks

• The Philippines and Indonesia account for 86 percent of the fish species imported into America for use in public and private aquaria.

• Some fish populations such as the Yellow Tang are down by 70 to 90 percent in their natural habitat as a direct result of collection for aquaria.

What many don’t understand is that removing fish in such large quantities can have significant impacts on the balance of the natural ecosystem. The ocean food chain rests on a delicate balance, and disrupting it this much with the removal of one species in particular can have profound effects on the growth and reduction of other species in the food chain.

There is also a lack of understanding when it comes to the distress and pain of the animals being removed from their natural environment. The stress of transportation alone can significantly reduce the life span of any marine species. Imagine the stress levels you’d endure if you were to be suddenly kidnapped, relocated and then forced to live in inferior conditions without any contact with your family or friends?! Pretty scary we think you’ll agree!

Any Yes’s in the House?

Admittedly the picture we’ve painted so fair seems to provide fairly damning evidence. However let’s consider the opposing view, as it’s not impossible that a properly operated aquarium – if equipped with the correct ethical and moral standards – could have a positive effect on conservation and education. Again we can go back to the example of early life marine interactions inspiring the next generation to become divers, conservationists and marine biologists. But of course not all divers were motivated by marine attractions. Most of us developed a love of the ocean through independent travel and exploration. And here on Koh Tao certainly, it’s easy to forget that not everyone is as lucky as we are to see amazing marine life in its natural environment on such a regular basis. It’s virtually impossible to imagine the same feeling of excitement and joy that courses through us when we see a Whale Shark, for example, if that experience was to happen in an artificial environment. Of course part of the excitement for divers is the sheer luck involved in being at the right place at the right time to see one, but that’s all part of the diving psyche.

The Changing of Attitudes

As the famous Baba Dioum quote goes:

“In the end we will conserve only what we love. We will love only what we understand. We will understand only what we are taught.”

So there is certainly a case to be made that there is an educational purpose. This can be backed up by many conservationists who have previously worked or volunteered in the industry:

“I worked for a year at the SEA LIFE London Aquarium in England. There, I watched children enter the aquarium afraid of sharks and leave, some hours later, aware of the threats that face sharks, and determined to help with their conservation.” Jessica McDonald, 2017

There are many like Jessica, who admit that quality aquariums can turn fear to respect, and that by promoting conservation and education with younger visitors, they can help raise awareness. This is something that perhaps is difficult to get our heads around as avid ocean lovers already. However studies have shown that for those with a lower understanding or existing familiarity, concern about marine life and marine conservation in general can be significantly increased after visiting aquariums.

Conservation & Research

There are some public aquarium facilities that do great conservation and research work – such as the rehabilitation of sick and injured animals for release back into the wild, or the tagging and monitoring of animals for the purpose of research into improving legislation and fishing policies. In these circumstances, given proper management and transparency in their operations, one could argue that the existence of such facilities is indeed a tool for improving the lives of marine life and raising awareness. Don’t be misled though, because of all zoos, aquaria and dolphinaria, it’s estimated that no more than 10% have any kind of significant conservation programmes. Plus there is a distinct shortfall in the numbers of conservation-priority species being studied to make an impact. So most would argue that when captive marine life is on public display, it is not possible to claim that conservation is the primary purpose of any facility . And in any case, does any kind of knowledge or development gained justify the collection and entrapment of marine species from their natural environments?

A current example of a facility that houses marine life under the pretense of conservation, but unfortunately appears to be more of a money making opportunity, is the Bear Grylls Adventure Park, opening near the city of Birmingham in the UK. It is disappointing to see someone widely considered an advocate of the natural world, to be so shortsighted in actively promoting keeping marine life in captivity. Dr Schubert of the Animal Welfare Institute believes the adventure park will send out the entirely wrong message to the public about how to interact with wildlife, and how marine animals should be treated:

“It’s designed to provide a thrill for people — not help sharks.” DJ Shubert, 2018

We agree with Dr Shubert, and find it sad that a celebrity with so much potential for doing good, would take such a step backwards – especially in an age where awareness about animal welfare is at its peak. Should you agree too, we invite you to join us in signing this petition.

Access to Marine Life

Most people are not as lucky as us, and don’t get to live in the tropics and swim around with fantastic creatures on a daily basis. So for many, aquariums, parks and zoos represent the only way – and certainly the most cost effective way – to have any kind of interaction with marine life.

What’s the Verdict?

We’ll leave you to make up your own minds, but you can probably already tell which side of the argument we come down on! We’re not saying there are no facilities that have good intentions or valid conservation programmes, just that these will be very few and far between. And certainly you’d never see us near a facility that houses cetaceans and/or large pelagic species like sharks!

It’s such a hotly debated topic though, and we are interested in your views! So what do you think? Have you been to an aquarium, park, zoo or other attraction that houses captive marine life? How did you feel about it? Would you go back? Let’s say you are with a large group of friends or family members who’ve planned a trip to an aquaria. Would you go? Or rather convince them to do something different instead? Please feel free to leave comments of your own or ask questions in the comments section.